Order the Winter 2025 issue of Nimrod International Journal or subscribe today.

Poetry isn’t “serious.” Here I’m citing the philosopher J. L. Austin, who puts the words “serious” and “seriously” in scare quotes on the multiple occasions when, in his lectures on speech act theory, he explains that a poem—like a joke, and like an utterance performed by an actor on stage—simply can’t be serious. (Christopher Ricks calls these quotation marks “prophylactic,” like a bubble around seriousness to protect it from the malignant unseriousness of poetry that threatens to infect and invalidate all our speech acts.) In Lecture I of How to Do Things with Words, Austin defines the performative utterance with what he calls a “vague” rhetorical question—a device that, like scare quotes and parentheses, leaves us uncertain about its seriousness: “Surely the words must be spoken ‘seriously’ and so as to be taken ‘seriously’? This is, though vague, true enough in general—it is an important commonplace in discussing the purport of any utterance whatsoever. I must not be joking, for example, nor writing a poem.”

Austin’s yoking of poems with jokes in a hendiadys for unseriousness, a yoke that is itself a joke, might be taken as a troll of poetry scholars. (If it was, it worked: Ricks is hardly the only one who has, good-humoredly in his case, taken the bait.) But it might also be understood as an insight into the social function and formal functioning of short first-person poems, which, like jokes, can be offered up as a way of both saying and not saying what one feels, of neither affirming nor lying, where a volta can turn into a punchline. Adding to this conflation or confusion, many people today get their jokes and their poems from the same place: social media, especially Twitter and Instagram.

On Twitter, perhaps more than anywhere else, jokes are poems and poems are jokes, giving rise to a digital culture of literary criticism that affords one-liners the same attention as lines of verse. In appreciative quote-tweets, users admire the verbal economy of each other’s viral jokes, their cadences and surprising word choices, their allusions to posts of yore. The semi-anonymous poster Dril has more than once been referred to as the site’s poet laureate. Canonical poems, most notably William Carlos Williams’s “This Is Just to Say,” have been re-canonized as memes and taken up, in turn, as creative writing prompts. Any trending topic on Twitter is likely to produce a crop of faux-apologies in Williams’s style (“This is just to say / I stole / the election / that you were probably / saving / for democracy”); according to one of multiple New York Magazine articles on this phenomenon, the format goes back to Twitter’s earliest days but really took off when the site enabled line breaks in 2013. Line breaks, the defining feature of poetry for Giorgio Agamben and for many Rupi Kaur defenders, have also been used by some of the most already-mocked Twitter accounts to unintentional hilarity-enhancing effect. Elon Musk’s rhyming paean to religion (“Atheism left an empty space / Secular religion took its place / But left the people in despair / Childless hedonism sans care / Maybe religion’s not so bad / To keep you from being sad”) has been hailed by one Twitter critic, Ben Flores, as “one of the worst pieces of writing of all time.” Jordan Peterson’s recent experiments with enjambment (e.g., “Everything is an infant / To a childless woman”) have earned him multiple comparisons to Kaur. This honor has also been bestowed upon the pseudonymous Airline Manager in the Eric Adams indictment (“Why does he care? / He is not going to pay / His name / will not be on anything / either”), which in turn generated a textbook version of “This Is Just to Say” (“This is just to say / I have paid / your hotel expenses / at Four Seasons…”). When someone starts writing like they’re writing a poem, whether they mean to be funny or not, it’s a joke.

The humor in these cases comes from the premise that when Elon Musk, Jordan Peterson, or Rupi Kaur sits down to write a few lines of what could be construed as verse, they are trying and failing to be serious. Bad poetry is, like camp, failed seriousness. But that doesn’t mean good poetry is necessarily successful seriousness. Here’s Austin again, giving us an example, in Lecture VIII, of the difference between efficacious speech acts and “not serious” utterances, such as “joking,” “acting a part,” or “writing poetry”:

For example, if I say “Go and catch a falling star,” it may be quite clear what both the meaning and the force of my utterance is, but still wholly unresolved which of these other kinds of things I may be doing. There are aetiolations, parasitic uses, etc., various “not serious” and “not full normal” uses. The normal conditions of reference may be suspended, or no attempt made at a standard perlocutionary act, no attempt to make you do anything, as Walt Whitman does not seriously incite the eagle of liberty to soar.

The “I” in Austin’s first sentence is better known as John Donne; the quotation comes from an untitled “Song.” Partly because it’s unattributed, it doesn’t look like a serious quotation; it sounds made up, the kind of thing a philosopher would say when coming up with the kind of thing a philosopher would say (“For example, if I say…”). That preface works a bit like a bracketed “(poet voice)” at the beginning of a parodic tweet, or like a deflationary “Poets be like” quote-tweet of the earnest exhortation of an amateur astronomer to “Go look at the moon right now.” “I love you,” Austin seems to be saying to poets, “but you are not serious people.” One thing Austin has in common with Twitter posters is that when he uses someone else’s line without attribution, he is attempting to make the reader “go and catch” something: the reference.

The critic Barbara Johnson, in her discussion of Austin’s dismissal of poetry, drama, and jokes as not “serious,” points out how surprisingly silly his “Go and catch a falling star” example is, because even within the poem, the speaker is so obviously not being serious. The command is self-consciously infelicitous: as the poem goes on, it becomes clear he’s saying that catching a falling star is as impossible as finding a chaste woman, which, if you know as much about that as Donne does, you know is quite impossible. As Johnson puts it, “The very non-seriousness of the order is in fact what constitutes its fundamental seriousness,” because it’s sounding the alarm about a national emergency of female sexual promiscuity. To Donne, though, female sexual promiscuity is itself a joke, one he reiterated across his poems in such various ways that the punchline of a given poem might be less that all women are false than that he has somehow found a way to reach that conclusion yet again, and from such an improbable opening as, say, “Go and catch a falling star.”

Johnson quotes a different version of Austin’s falling star example from the one I’ve quoted. Hers is drawn from “Performative Utterances,” a talk delivered in 1956, the year after Austin delivered the lectures that would become How to Do Things with Words. There, Austin still doesn’t name Donne, but it’s no longer he himself who’s hypothetically speaking: this time he says, “If the poet says ‘Go and catch a falling star’ or whatever it may be, he doesn’t seriously issue an order.” It’s as if Austin is retracting his identification with the lyric “I” and making clear that he, a philosopher, would never say something so stupid, although of course a poet would. Ricks, who also cites this version, finds the “whatever” particularly funny: “the effect […] is to intimate, wearily, that not only does the poet not seriously issue an order, the poet does not seriously issue anything.” The poet is not merely prone to unserious behavior but is, in his very essence, to borrow a devastating insult serious Twitter users often level against their enemies, “deeply unserious.”

And indeed, maybe poetry, and especially lyric poetry, just isn’t that serious. But, of course, it used to be so serious: for much of the twentieth century, it was arguably the only genre to be really taken seriously in academic literary criticism, and for centuries before it captivated philosophers seeking insight into the nature of language, of subjectivity, and of history. For Hegel, the fact that lyric “can take as its sole form and final aim the self-expression of the subjective life” meant that the poet was a world unto himself: “it is the intuition, feeling, and meditation of the introverted individual, apprehending everything singly and in isolation, which communicate even what is most substantive and material as their own, their passion, mood, or reflection”; in Colin Burrow’s gloss, “Spirit strutted its stuff” in lyric. For John Stuart Mill, who associated narrative fiction with children, “idle and frivolous persons,” and nations arrested in “the childhood of society,” lyric was the only literary form fit for serious adults and adult civilizations. For Paul de Man, the study of lyric can reveal something about “the nature of modernity” unavailable to us from any other source, despite or because lyric is “an enigma which never stops asking for the unreachable answer to its own riddle.” Aristotle’s dictum that “poetry is more philosophical and more serious than history,” dealing as it does with general possibilities rather than particular facts, could serve as a slogan for the New Critics and other midcentury theorists who saw the lyric poems of the Renaissance and Romanticism as sites for working out the most serious philosophical problems—the particular fact that Aristotle was referring to dramatic poetry, rather than lyric, notwithstanding. Such literary critical scriptures as “The Intentional Fallacy,” where “author” and “poet” are used interchangeably, take as an article of faith that lyric is the only literature worth taking seriously. For other readers, academic and otherwise, what makes lyric so serious is precisely the poet’s intention, as famously articulated by Mill: “Poetry is feeling confessing itself to itself in moments of solitude, and embodying itself in symbols which are the nearest possible representations of the feeling in the exact shape in which it exists in the poet’s mind.”

Lyric’s seriousness, then, is at once a self-seriousness—an oft-assumed identity between poet and speaker, the assumed sincerity of the poet-speaker’s expression—and a kind of selfless seriousness: the lyric “I” is a generic subjectivity, a pronoun taken on by the reader who recites the poem, a persona that speaks in the present tense across time, or a writer, in Helen Vendler’s words, “so unconscious of his reader that we have only the choice of becoming him […] and losing our own identity.” Lyric’s timelessness, some argue, is what has recently made it untimely. In Professing Criticism, his historical survey of academic English literary studies in the U.S., John Guillory claims that the recent emphasis on presentism and “topicality” in university curricula has meant that lyric and other old poetic genres have been supplanted by something newer, sexier, more political—namely, prose narrative. The flip side of lyric’s lofty transcendence of the political moment is its embarrassing irrelevance.

And yet more people are reading and publishing poetry today than ever before, most often online. Ryan Ruby, referring to this fact in his recent Context Collapse, a brief history of poetry written, as a kind of joke, in very loose blank verse, argues that it is “a basic law of economics / That makes poetry seem irrelevant / At the peak of its popularity / And causes its cultural stock to crash.” Virginia Jackson has argued that the New Critics and their ilk redefined “poetry” as “lyric” and “lyric” as whatever you could fit on a handout, slide in front of an undergraduate, and ask them to close read. Now it’s whatever you can fit in a screenshot, whether you’re an Instapoet formatting an original composition, a content curator hoping to go viral by being the millionth person to post Maggie Smith’s “Good Bones,” or a shitposter cropping a legal document to look lineated.

Perversely, the immediacy of lyric on social media, especially Twitter and Instagram, has led to a new, or renewed, lyric seriousness: a somewhat archaic sense of lyric’s ability to act not on the mind, but directly on the world and on the body, as if we were in the presence not of a metaphorical well-wrought urn but of the well-tuned lyre itself. On Poetry Twitter, users relate the visceral effects poems have had on them: “this destroyed me”; “this gutted me”; “this broke me”; “this knocked me out”; “I wish I could scratch this poem on the inside of my eyelids.” Canadian academic and prolific viral-poem-dunker David Hollingshead posted a tweet mocking the mismatch between those serious injuries and the unseriousness of the poems that accompany such captions: “poetry Twitter will be like ‘this unraveled me’ and the poem is ‘the wild baboon / of my heart / is loose / with a taser / at Six Flags.’” Hollingshead recently quote-tweeted this years-old post of his from a previous account, since lost to the vagaries of time and Twitter terms of service, with the caption, “my one evergreen tweet”: a Petrarchan laurel for our time.

The circulation of explicitly political short poems on social media in response to world events—Ross Gay’s elegy for Eric Garner, “A Small Needful Fact,” following the murder of George Floyd; Ilya Kaminsky’s “We Lived Happily During the War” following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—has attested to another sense of lyric’s seriousness. Reacting against the (inaccurate) assumption that lyric has always been a private and apolitical affair—“feeling confessing itself to itself,” an utterance that is “overheard” rather than directly addressed—modern and contemporary poets have emphatically defined lyric as public and urgently relevant, an orientation exemplified by the title and subtitle of Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric. If poems like Gay’s and Kaminsky’s have been less forthcoming on Twitter following the 2024 U.S. Presidential election, it might be because the site itself has become impossible to take seriously, or even unseriously.

But what if a lyric poem is neither successfully intervening in a serious national conversation, nor missing the mark of seriousness, but is literally joking? What if I were joking, for example, and writing a poem—as, I think, Donne often was? What if the poem is a serious joke? This question was raised by Noah Mazer’s “Liberal Poem for Palestine,” published in Protean Magazine in March 2024 and quickly republished on Twitter, where its lo-cap, Kaur-adjacent aesthetic helped it go viral:

the guerrilla moves among the people

as a fish swims through water

i sit by the river

i condemn the fish.

i condemn the water.

The poem starts with a silent quotation of Mao’s famous dictum about how the guerilla moves among the people. It then introduces a first-person speaker who performs a speech act: the serious act of condemnation (“i condemn the fish. / i condemn the water.”), punctuated by periods, like Boomer text messages. This spin on an unquoted quote works a bit like what are called on Twitter copypastas or snowclones: unmarked phrasal templates that are repeated verbatim, minimally altered, or recontextualized. The speaker in this satirical poem is not, of course, identical with the poet, who is making a joke out of liberals’ impulse to condemn—to perform speech acts that, in their circumstances, are invalid, effectively impotent, despite the fine points they try to put on them.

Alex Colston, a graduate student in clinical psychology and editor of the magazine Parapraxis, posted a screenshot of the poem to the tune of 15,000 likes, along with a range of comments and quote-tweets. Some took the poem, and its acts of condemnation, seriously. Within this group, some judged it bad or corny, or complained about the lack of capitalization or rhyme; one called it a “war crime.” One said, “I thought this was a joke,” but apparently then thought better of it. Others translated it into Spanish, Portuguese, Turkish, and other languages, following the model of the outpouring of spontaneous Twitter translations of the Palestinian poet Refaat Alareer’s “If I Must Die” into dozens of languages after Alareer was killed by an Israeli airstrike in December 2023. Colston followed up on his viral screenshot to say: “The effect this poem is having in my replies is so fucking funny. Please learn how to read (a poem), lmao.” Both the poem and the replies to the poem, when properly read, will produce the same interpretation, the upshot of which is: lmao.

Another poem about Palestine, this one by Brooklyn-based writer Vinay Krishnan, also went viral on Twitter last spring. Mocked as the “real ‘Liberal Poem for Palestine,’” the post-facto object of Mazer’s parody, it expresses the cognitive dissonance of witnessing genocide while going about one’s day as a member of the coastal-elite creative class. The poem’s title, and first and last line, “There’s laundry to do and a genocide to stop,” became a snowclone: “there’s laundry to do and a bad poetry epidemic to stop”: “there’s laundry to do and a DoorDash driver to berate”; “there’s laundry to do and MY PUSSY IN BIO.” These parodies piled up like laundry, or like the paratactic lines of Krishnan’s prose poem.

But the poem got a full-throated tweeted defense from the writer Aaron Bady, who accused its haters of willed illiteracy (“I think most of the people who got mad at it barely read it once, if that”) and an unhealthy addiction to metadiscourse: people didn’t hate the poem so much as the kind of poem it had been collectively identified to be, and the praise it received. We’re eager to read the phenomenon of bad poetry on Twitter without reading the poems themselves. Bady concludes, “Of course, what are we all doing here on twitter dot com […] except doing all the things that people used to do in poetry? we’re making jokes, noting world events, zinging each other, being sincere, horny, or sad.” “But of course,” he followed up in the next tweet in his 17-tweet thread, “no one takes tweets very seriously.” As one anonymous user recently replied to a linked article about Elon Musk’s devotional couplets, “It was just a tweet bro. Calm down.”

How seriously we should take tweets has been a pressing question for employees facing termination for posts they may or may not have meant seriously and for politicians facing legal consequences for posts inciting violence. Even in less charged situations, the formal conventions of Twitter, not unlike those of lyric, both establish and undermine an authoritative persona, making it deceptively difficult to establish intention. The site is overrun with citation, those copypastas and snowclones, so that authorship often means taking on the authority of another. The phrase “There are cathedrals everywhere for those with eyes to see”—a caption often applied to images where, for example, a bar graph resembles the silhouette of Saddam Hussein in his hiding place in a much-memed newspaper graphic, or an ear of corn with rust-colored silk cascading over its husk resembles Chappell Roan—has been assumed to derive from a source such as William Blake or Marcel Proust; it is in fact a Twitter-native utterance, an observation made by Jordan Peterson about the light hitting the embossed plastic of his Evian bottle. There are “There are cathedrals everywhere for those with eyes to see” everywhere for those with eyes to see, textual templates that have drifted from their original context and taken on new meaning through reuse. In addition to the journalists, politicians, activists, sexbots, and Nazis, Twitter is populated by amateur textual and visual formalists. As Michael Dango observed in a 2019 Los Angeles Review of Books essay on the site’s heavy traffic in memes, meme-makers display the kind of reading skills, the facility with pattern and allusion, that we often lament our literature students lack, even though many of them may in fact be sitting in our literature classes, ignoring our lectures and making memes instead. They recognize formal outlines that can be manipulated and filled; they take on other voices; they identify with images. When inhabiting the purely conventional authority of a meme template, or even the more ordinary and less marked phrasal templates of Twitter discourse (every academic’s least favorite of these is “pleased to announce…”), is it even possible to speak as ourselves, or must we mean only what “the poet” might mean—that is to say, nothing serious?

Maybe, like Barbara Johnson says of lyric, the rhetorical power of tweets derives from their unseriousness: their slightness, their instantaneity, their refusal to commit to anything but a bit. As one of the masters of the form, Joyce Carol Oates, has said when asked how she managed to write novels while apparently on Twitter all day, “It takes 20 seconds to tweet. If you tweet five times a day, that’s just a few minutes, but it might seem to the observer like much more, like most illusions.” The poet Eileen Myles, in a 2015 interview with the Paris Review, suggested an almost opposite view: the unseriousness of Twitter, like that of most illusions, means that you can’t even tell when it’s taken over your language, when it’s become a parasite living inside you. “You may not use social media,” Myles warns, “but it’s using you. You’re writing in tweets, like it or not.” Later in the interview, they compare social media to “walking down the street in your connected notebook”—the solipsistic poet’s pad hooked up by a series of tubes to the street and to the world. While notebook-walking, “maybe a line comes to you—and it’s really hard to figure out what’s poetry and what’s a tweet at this time—but the line comes and […] you make the joke, Here’s the thing I saw and here’s the line that came to me and I’m sending this out to seven thousand people right now and I’m gleeful that I’m not alone in this particular way.” It may be really hard to figure out what’s poetry and what’s a tweet, but one thing Myles seems sure of, in 2015, is that they’re both jokes, and that “the line that came” to her can also come to us: something that, unlike a falling star, we can really go and catch.

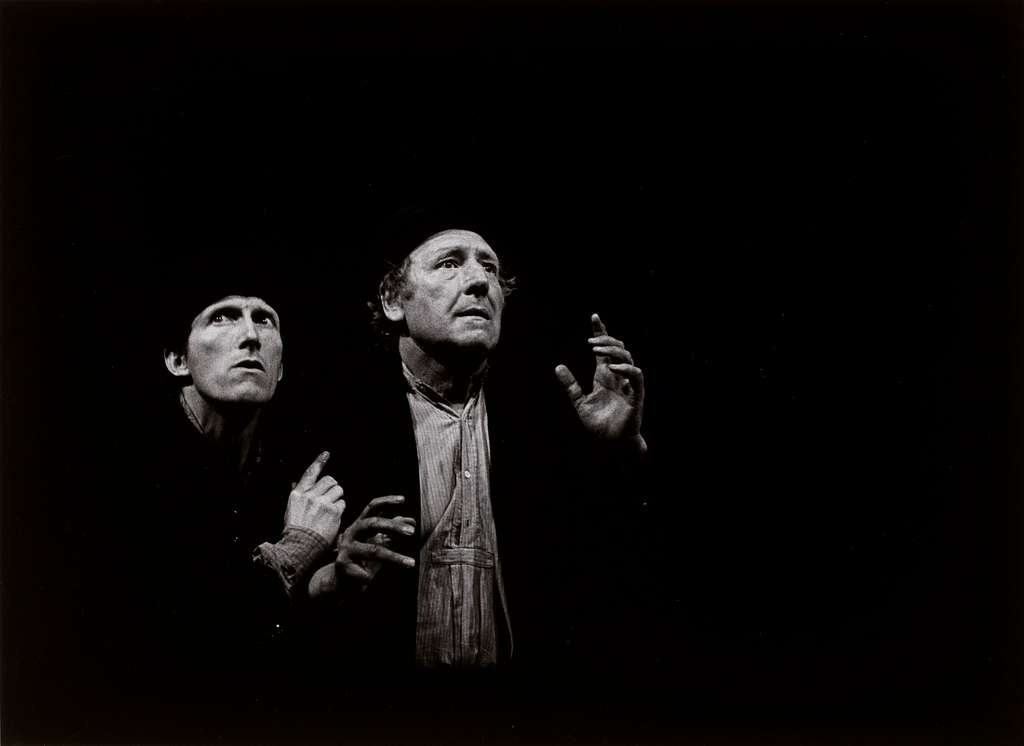

Something we can all be sure of is that it’s not 2015. Twitter, currently known as X, no longer feels like the connected notebook it once was. For users of Bluesky, an app initially developed in 2019 as internal research by Twitter that, following Musk’s purchase of the site, broke off as a competitor, Twitter is not the public square or the neighborhood hangout but “the Nazi bar,” or more specifically, “permanent open mic night at the Nazi bar.” Since Donald Trump’s election, which Musk helped engineer, and from which he has reportedly already earned massive profits, a familiar microgenre of tweet has re-emerged: the tweet of resignation. “I don’t know how much longer I can stay on this site.” “I’ll be deactivating. Find me on Bluesky.” “I’ll be posting at the other place. Goodbye.” At this time, too, it’s hard to figure out what’s poetry and what’s a tweet, in part because these declarations are so often unserious, followed up by more tweets, implicit repudiations of repudiation. “I never wish to sing again as I used to,” Petrarch sings in the 105th poem of his Canzoniere (he would go on to sing 261 more times). On November 7, someone posted an edited screenshot of Waiting for Godot that read: “ESTRAGON: Shall we log off? VLADIMIR: Yes, let’s log off. [They do not log off.]” The dialogue is lineated, so I’ll call it a poem.

Katie Kadue is an assistant professor of English at SUNY Binghamton. Her writing has appeared in publications including The New Yorker, Chronicle of Higher Education, Bookforum, and n+1.

Order the Winter 2025 issue of Nimrod International Journal or subscribe today.